Catching The Eye/Flickr, CC BY

Catching The Eye/Flickr, CC BYOn Churchill Island, southeast of Melbourne, small cone-shaped, shallow holes (digs) puncture the grass. They’re widespread, and reveal moist soil below the surface. A soil heap at the entrance of a dig is a sign it was made recently.

Older digs are filled with leaves, grass, spiders, beetles and other invertebrates. They are made by hungry eastern barred bandicoots – small, roughly rabbit-sized digging marsupials – looking for a juicy worm or grub.

Read more: How you can help – not harm – wild animals recovering from bushfires

It turns out these bandicoot digs are far from just environmental curiosities - they can improve the properties and health of soils, and even reduce fire risk.

But eastern barred bandicoots are under threat from introduced predators like foxes and cats. In fact, they’re considered extinct in the wild on mainland Australia, so conservation biologists are releasing them on fox-free islands to help establish new populations and ensure the species is conserved long-term.

Our recent research on Churchill Island put a number on just how much the eastern barred bandicoot digs - and the results were staggering, showing how important they are for the ecosystem. But more on that later.

A dig from an eastern barred bandicoot.Amy Coetsee

A dig from an eastern barred bandicoot.Amy CoetseeWhy you should dig marsupial diggers

Digging mammals – such as bettongs, potoroos, bilbies and bandicoots – were once abundant and widespread across Australia, turning over large amounts of soil every night with their strong front legs as they dig for food or create burrows for shelter.

Read more: Restoring soil can help address climate change

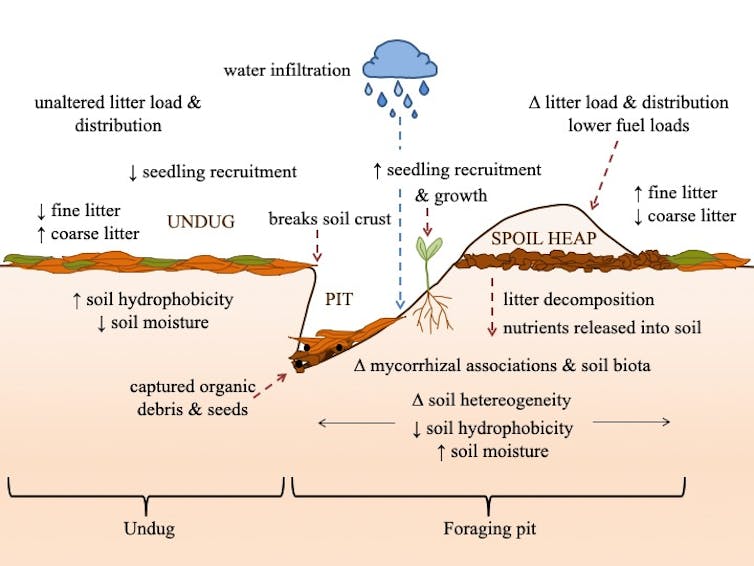

Their digs improve soil health, increase soil moisture and nutrient content, and decrease soil compaction and erosion. Digs also provide habitat for invertebrates and improve seed germination.

What’s more, by digging fuel loads (dry, flammable vegetation, such as leaves) into the soil, they can help bring down the risk of fire.

Rather than leaves and other plant matter accumulating on the soil surface and drying out, this material is turned over faster, entering the soil when the badicoots dig, which speeds up its decay. Research from 2016 showed there’s less plant material covering the soil surface when digging mammals are about. Without diggers, models show fire spread and flame height are bigger.

In fact, all their functions are so important ecologists have dubbed these mighty diggers “ecosystem engineers”.

How bandicoot digs affect soil.Leonie Valentine, Author provided

How bandicoot digs affect soil.Leonie Valentine, Author providedLosing diggers leads to poorer soil health

Of Australia’s 29 digging mammals, 23 are between 100 grams and 5 kilograms. Most are at risk of cat and fox predation, and many of these are officially listed as threatened species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Since European settlement, six of Australia’s digging mammals have gone extinct, including the lesser bilby, desert rat kangaroo and pig-footed bandicoots. Many others have suffered marked population declines and extensive range contraction through habitat destruction and the introduction of foxes and cats.

Read more: Rockin' the suburbs: bandicoots live among us in Melbourne

Tragically, the widespread decline and extinction of many digging mammals means soil and ecosystem health has suffered as well.

Soils that were once soft textured, easy to crumble, rich and fertile are now often compact, repel water and nutrient poor, impeding seed germination and plant growth. Fuel loads are also likely to be much higher now than in the past, as less organic matter is dug into the soil.

To date, most research on digging mammals has focused on arid environments, with much less known about how digging influences wetter (mesic) environments. But our recently published study on eastern barred bandicoots provides new insights.

Just how much do bandicoots dig anyway?

In 2015, 20 mainland eastern barred bandicoots were released onto Churchill Island in Victoria’s Westernport Bay.

When eastern barred bandicoots were released on Churchill Island.On mainland Australia, fox predation has driven this species to near extinction, and it’s classified as extinct in the wild. All Victoria’s islands are beyond the historic range of eastern barred bandicoots, but fox-free islands could be how we recover them.

Introducing bandicoots on Churchill Island presented the perfect opportunity to quantify how they influence soil properties when digging for food.

Read more: The secret life of echidnas reveals a world-class digger vital to our ecosystems

To do this we recorded the number of digs bandicoots made each night and measured the volume of soil they displaced through digging. We also compared soil moisture and compaction within the digs, versus un-dug soil – and we didn’t expect what we found.

In one night on Churchill Island, one bandicoot can make 41 digs an hour. That’s nearly 500 digs a night, equating to around 13 kilograms of soil being turned over every night, or 4.8 tonnes a year. That’s almost as much as the average weight of a male African elephant.

Bandicoots turn over huge amounts of soil in their search for food.Amy Coetsee

Bandicoots turn over huge amounts of soil in their search for food.Amy CoetseeSo, an astonishing amount of soil is being turned over, especially considering these bandicoots typically weigh around 750 grams.

If you multiply this by the number of bandicoots on Churchill Island (up from 20 in 2015 to around 130 at the time of our study in 2017), there’s a staggering 1,690 kilos of soil being dug up every night. That’s some major earthworks!

However, we should note our study was conducted during the wetter months, when soils are typically easier to dig.

In summer, as soil becomes harder and drier on Churchill Island, digging may become more difficult. And bandicoots, being great generalists, feed more on surface invertebrates like beetles and crickets, resulting in fewer digs. So we expect in summer that soil is less disturbed.

Bandicoots might help agriculture too

All this digging was found to boost soil health on Churchill Island. This means eastern barred bandicoots may not only play an important role in ecosystem health and regeneration, but also potentially in agriculture by assisting pasture growth and condition, reducing topsoil runoff, and mitigating the effects of trampling and soil compaction from livestock.

One of 20 eastern barred bandicoots being released on Churchill Island.Zoos Victoria

One of 20 eastern barred bandicoots being released on Churchill Island.Zoos VictoriaThe benefits bandicoot digs have across agricultural land is of particular importance now that eastern barred bandicoots have also been released on Phillip Island and French Island, and are expected to extensively use pasture for foraging.

These island releases could not just help to ensure eastern barred bandicoots avoid extinction, but also promote productive agricultural land for farmers.

Read more: To save these threatened seahorses, we built them 5-star underwater hotels

So, given the important ecological roles ecosystem engineers like bandicoots perform, it’s also important we try to reestablish their wild populations on the mainland and outside of fenced sanctuaries so we can all benefit from their digging, not just on islands.

Lauren Halstead is the lead author of the study reported, which stemmed from her honours research at Deakin University. She also contributed to the writing of this article.

Euan Ritchie receives funding from the Australian Research Council, The Australia and Pacific Science Foundation, The Hermon Slade Foundation, Australian Geographic, Parks Victoria, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, and the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC. Euan Ritchie is a Director (Media Working Group) of the Ecological Society of Australia, and a member of the Australian Mammal Society.

Amy Coetsee works for Zoos Victoria, a not-for-profit zoo-based conservation organisation.

Anthony Rendall is a member of the Australian Mammal Society

Duncan Sutherland works for the Phillip Island Nature Parks, a not-for-profit self-funded conservation organisation, and receives funding from the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust, Department of Environment, Land Water and Planning, and the Penguin Foundation. Duncan Sutherland is a member of the Ecological Society of Australia and the Australian Mammal Society.

Leonie Valentine works for the University of Western Australia and receives funding from the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub (NESP - TSR). Leonie Valentine is an Associate Editor of the journal Austral Ecology, a member of the Ecological Society of Australia and the Australian Mammal Society.

Authors: Euan Ritchie, Associate Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|